[What a rich source of systems thinkers and systems thinking the OU courses have been!]

[Update: apologies, Helen has pointed out that I put the whole article here without the Creative Commons license – my mistake! It is below.

NB 1, I feel I should probably do short intros to pieces and then a link to the original, which would make the front page easier to scan and redirect more people to the original – my failure to do this often is down to laziness and not being certain where to create the ‘fold’ and stop the content. I’ll try to break that bad habit.

and, 2, I suspect it would also be clearer and easier if I put the ‘link to source’ at the top of the post – the browser plugin I use, ‘press this’, automatically puts it at the bottom, below a sample (badly formatted, no images) of the content. Will try to change this too]

Creative Commons Licence

Just Practicing by Helen Wilding is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Recently I wrote a post on Situations which ended as follows:

But, in spite of all the commonalities, there is a distinction in the way that TU811 treats situations of interest compared to the way TU812 treats situations of concern…

In TU811, it is perfectly possible to adopt a first order stance – using systems approaches to analyse a situation of interest that you stand apart from. You can take the mindset of a consultant asked to advise or make recommendations to someone in government or in an organisation. It is possible to be objective and distant, to lack ownership of and for the situation. I say possible, you don’t have to engage with the situation that way but you can still engage pretty effectively as a systems practitioner if you do.

In comparison, when TU812 talks of situations of concern, they tend to be situations you experience directly – something you are part of. This means a first order stance is more constraining and it is more appropriate to adopt a second order stance. Here your personal engagement with the situation and the other people who are part of it matters. Your emotioning, understandings, actions and interactions can have an influence on whether the situation improves or declines. Your own action and interaction matters.

In the last few days, I have been reflecting on this in the light of closer reading of the work of Ison (2017) and various works by Checkland (e.g. 1985) which formed the basis for Ison’s conceptual model of what it is to think about practice.

The particular aspects I have been reflecting on are the way in which the practitioner and the situation can be perceived to relate to each other.

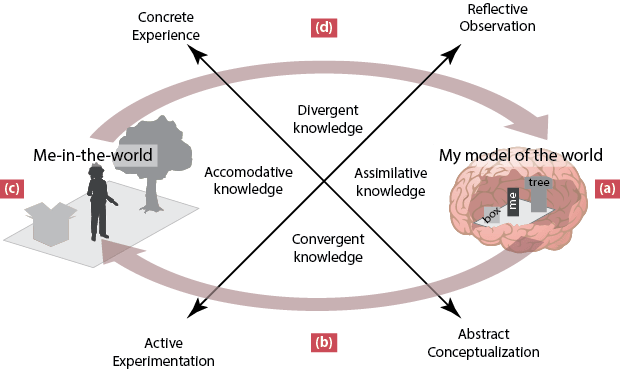

In Checkland’s various diagrams of the nature of research, his SSM model and the LUMAS model, the practitioner(s) doesn’t always get much prominence – when they do appear they are also sometimes referred to as a user(s) of a methodology. In general though, the practitioner is depicted apart from the situation, engaging with it from a distance (as in my Figure a).

Ison (2017) also depicts the relationship in this way in his Figure 3.5 (p.50) which aims to elucidate what happens when a practitioner thinks about their practice – a dynamic which involves a practitioner (P) engaging with a situation (S) with a framework of ideas (F) and a method (M) (the PFMS model)

When I wrote the previous blog, I concluded that it is sometimes more appropriate to adopt a second order stance – to recognise that you are part of the situation (as in my Figure b).

My recent insights have arisen from reading the the explanations that Ison (2017) gives when talking about the PFMS model (enhanced by some prompts in some personal correspondence with him).

He emphasises that all practice is situated, which changes the text in my Figure b to Figure c.

Ison (2017) isn’t alone in bringing attention to the situated nature of practice. I also like the explanation of Kemmis et al (2014) who coin the term ‘practice architectures’ to refer to the arrangements that afford certain practices and constrain others. Three different arrangements can be distinguished:

“Cultural-discursive arrangements that support the sayings of a practice, material-economic arrangements that support the doings of a practice, and social-political arrangements that support the relating of the practice. These arrangements […] hold practices in place, and provide the resources (the language, the material resources, and the social resources) that make the practice possible” Kemmis et al (2014, p.110)

But I get a sense that Ison (2017) is emphasising something different to Kemmis et al (2014). Rather than consider the situation as the context of the practice, it is more that ‘the situation’ is one particular element of practice (alongside P, F and M) worth understanding. He states:

“If you are alert you will recognise that this figure [i.e. his Figure 3.5] abstracts the practitioner (P) out of the situation (S) [as in my Figure a], yet I said at the beginning of this chapter that all practice is situated. To hold on to my claim I must ask you to imagine an animation in which the practitioner (P) and all the other elements, begin inside S [as in my Figure c]; what [the figure] depicts is an expanded abstraction from these initial conditions”. (p.50)

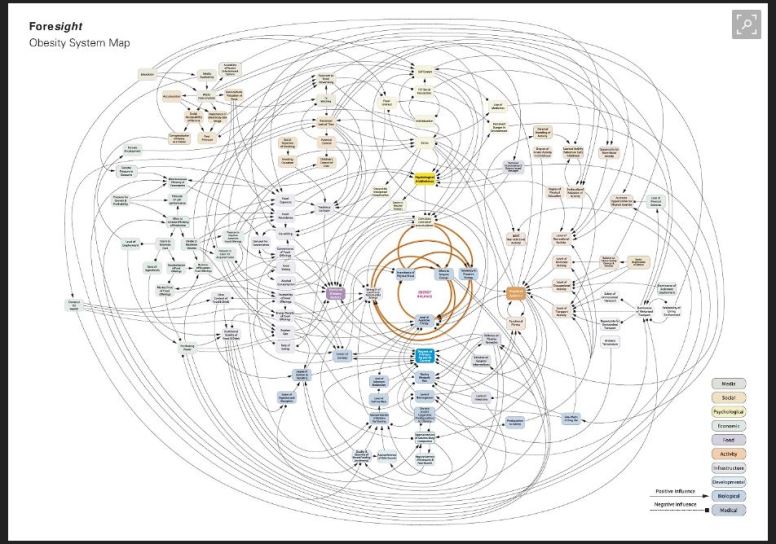

So the situation (S) in Ison (2017)’s depiction is best thought of as the situational element of practice. This is different to what I have been thinking – I think I have thought of it more like Checkland uses it in terms such as ‘research area’ or ‘the problematic situation’ – the issue that the practitioner is investigating or wanting to intervene in (like concerns about obesity or youth violence). This is also informed by my use of ‘situation of interest’ during TU811 as per the previous blog I refer to above.

There are similiarities of course – a practitioner may want to understand and act purposefully to change the situational element of their practice and, in doing so, they need to recognise that it has a history and a future (or to draw on Vickers (as Checkland did) it’s helpful to consider it a flux of events and ideas changing through time).

There is a further step to take as well – another level of abstraction. Ison (2017)’s model includes a person (who may be the same as the practitioner) thinking about the practice dynamic. He refers to all that exists in the thought bubble as a ‘real world situation’ and makes the point that that is his preference in a footnote. So in that sense, the practitioner reflects on the ‘real world situation’ – that is, their practice (see my Figure d).

That ‘real world situation’ is messy and complex so Ison (2017) invites people to think about it in terms of four elements or components and their relationships – the practitioner (P), their framework of ideas (F), the methods they use (M) and the situational (S) element. This is a heuristic – a device that helps to explore the ‘real world situation’ that is my practice – it isn’t a description of practice itself.

So in my research ‘policy work practice and its development’ is the phenomenom I am interested in – I am not just thinking about it, I am researching it. I am not just thinking about my own practice, I am considering policy work practice in a more general sense. In Checkland’s terms, practice is my ‘research area’ and whilst I have been informed by all the ideas above so far I do actually need to more explicitly declare the framework of ideas that informed my choice of methodology and the way I have approached the literature and my data. That’s what I am currently struggling with – it’s something like my Figure e.

Figure e: A practitioner (researcher) reflecting on their research practice to examine policy work practice and its development

Enough mental gymnastics for today – I do need to come back to this though. There is another layer in there too – somewhere in the middle – that of the action research participants seeking to understand their practice – a process which generated data for me to analyse and create findings.

References

Checkland, P. (1985), From Optimizing to Learning: A Development of Systems Thinking for the 1990s. The Journal of the Operational Research Society, 36(9), pp.757–767.

Ison, R. (2017), Systems practice: how to act Second Edition., Milton Keynes/London: The Open University/Springer Publications.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R. and Nixon, R. (2014), The action research planner: doing critical participatory action research, Singapore: Springer Link. [electronic edition]

Source: Just Practicing − The practitioner and the situation

I’ve read a number of

I’ve read a number of

You must be logged in to post a comment.