Source: Advancing my systems change typology: considering scaling out, up and deep | Marcus Jenal

Marcus Jenal

Ruminations on systemic economic and social change

Advancing my systems change typology: considering scaling out, up and deep

Recently I started a series on the development of a typology of systems change (the two previous articles are here and here). In this post, I want to introduce the concepts of ‘scaling out’, ‘scaling up’ and ‘scaling deep’ developed by scholars of social innovation. I want to link these concepts to my earlier thinking around the systems change typology and update it based on the new insights from this literature. At the end I will also voice a little critique on innovation-focused approaches to systems change.

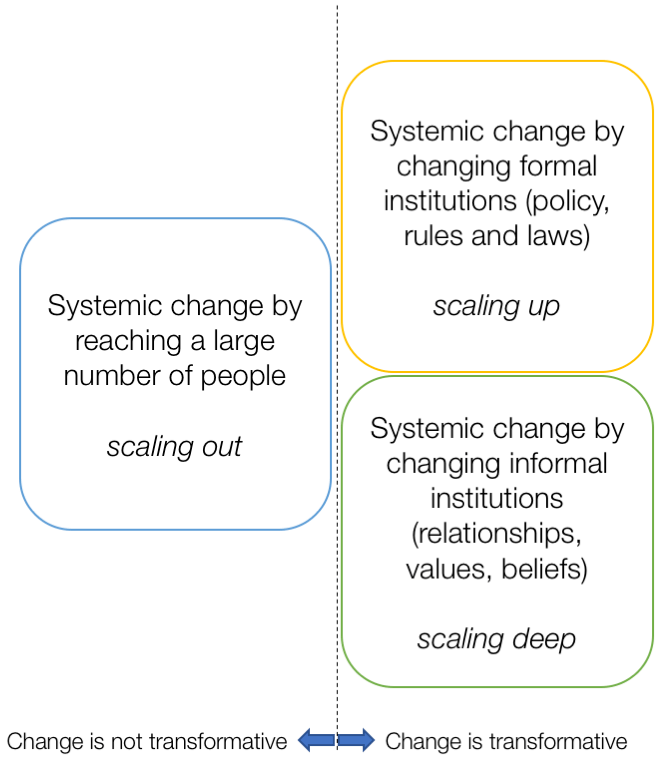

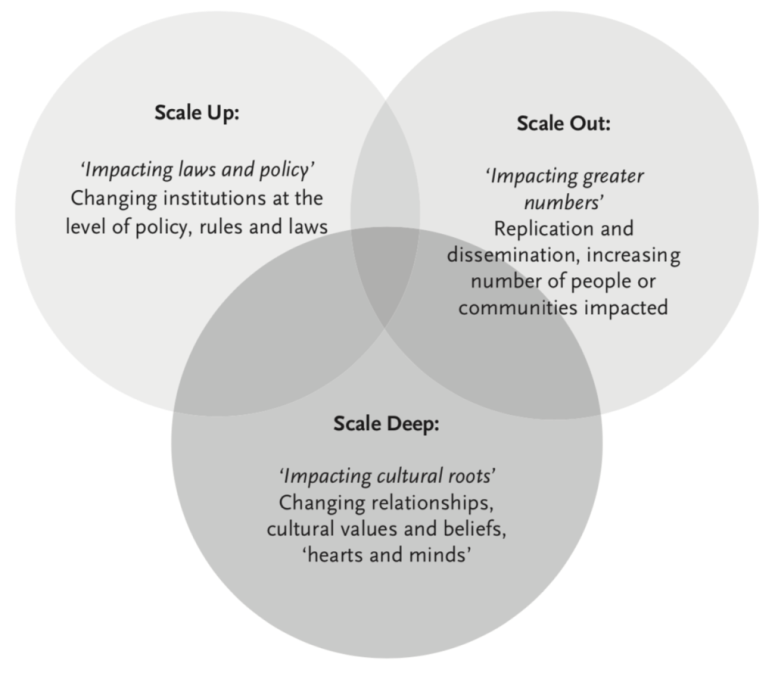

‘Scaling out’ refers to the most common way of attempting to getting to scale with an innovation: reaching greater numbers by replication and dissemination. ‘Scaling up’ refers to the attempt to change institutions at the level of policy, rules and laws. Finally, ‘scaling deep’ refers to changing relationships, cultural values and beliefs.

The differentiation between scaling out, scaling up and scaling deep was introduced by Michele-Lee Moore, Darcy Riddell and Dana Vocisano in a 2015 article in The Journal of Corporate Citizenship [1]. Moore and colleagues both draw from the literature – particularly the scholarly fields of strategic niche management (SNM) and social innovation – and from an empirical study they conducted with a number of grantees from the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation in Canada. SNM is a sub-field of the literature around socio-technical transition research I also refer to in my first article of the series.

In the outset of their article, Moore and colleagues ask [1:69]:

How can brilliant, but isolated experiments aimed at solving the world’s most pressing and complex social and ecological problems become more widely adopted and achieve transformative impact?

They then make the important point that … [1:69]

… [l]eaders of large systems change and social innovation initiatives often struggle to increase their impact on systems, and funders of such change in the non-profit sector are increasingly concerned with the scale and positive impact of their investments.

Hence, the starting point of the research is very similar to the one described by the Adapt-Adopt-Expand-Respond (AAER) framework (which I introduced in my first post in the series): a (social) innovation that is successfully addressing a particular problem or situation in one or a few specific contexts or niches.

Continues in source: Advancing my systems change typology: considering scaling out, up and deep | Marcus Jenal

License:

License:

Comments

Hillary Keeney and Bradford Keeney would like to express their gratitude and appreciation to our colleagues in Mexico for their support of this work. In particular Pedro Vargas Avalos and Clara Haydee Solis Ponce, who with their colleagues have sponsored our teaching at the Department of Clinical Psychology, National University of Mexico (UNAM), Zaragoza, and Juan Carlos García and Sylvia Arce, who have sponsored our teaching at Etfasis: Institute of Systemic Family Therapy. It was during our seminars there that many of the ideas in this book were developed.

Ronald Chenail would like to thank President George L. Hanbury II and Nova Southeastern University for supporting The Qualitative Report; Hillary and Brad Keeney for their continuing guidance and encouragement; Lydia Acosta, Michele Gibney, and Cheryl Ann Peltier-Davis for launching NSU Works and helping with our first book development and release; Melissa Rosen for her copyediting and graphics skills; Adam Rosenthal for his leadership in making TQR Books a reality; and Jan Chenail, my late wife, for making me a better writer, husband, father, and friend.

Copyright 2014: Hillary Keeney, Bradford Keeney, Ronald Chenail and Nova Southeastern University