Recent Updates Page 4

a new home for Krishan Mathis’ Viability Canvas at Tautai Salon

VSM and Viablity Canvas

VSM and Viablity Canvas

now at https://salon.tautai.net/

NEEDED: SYSTEMS THINKING IN PUBLIC AFFAIRS – Conway (2024)

h/t Ivo Velitchkov

Introduction

What is systems thinking? The answer depends on whom you ask. Here are two commonperspectives from which you will get two different answers. Engineering. Here, systems thinking is what you need to build a system whose requirements go beyond current practice. Example: all stages in a plan to evolve into a national energy distribution system for low-emission transportation. Metapolitics (a neologism analogous to metamathematics). Here, systems thinking is what you need (1)to understand the ambient social systems in which we all have unconsciously long been embedded, and (2)to use that understanding to attempt to bring these systems into alignment with current needs, given some disruptive change such as newtechnology or increased scale. Example: modifying the global economy in response to climate change.

This essay is based on the Metapolitics perspective. In two Examples I explore perverse behavior patterns of two ambient social systems, a newoneandanolder one: 1. mass radicalization, disinformation, and other perverse social consequences secondary to new technologies that facilitate intensive everyone-to-everyone communication (for example, “social networking”), and 2. environmental destruction secondary to a compulsion to grow arising from the financing structures of public corporations. Analysis of both of these behavior patterns reveals a common element: Emergent behaviors, not anticipated in classical thinking, arise from highly intraconnected or coupled networks. This failure of classical thought leads to The Big Lesson I wish to communicate in this essay: THINK NETWORKSFIRST, ACTORS SECOND. Here is the importance of this lesson: Effective interventions will arise from altering interactions within networks. You cannot even see these interactions unless you focus on the network. This essay offers two examples that contradict the conventional understanding of Network Effects. We are living inside something we don’t understand.

Peter Tuddenham on LinkedIn – mapping Claude’s eight conversation surfaces through the lens of Gordon Pask’s conversation theory

Peter writes:

“I’ve spent 40 years applying cybernetic frameworks to real organisations — from the U.S. Army War College to UNESCO to distributed educator networks spanning 18,000 participants. Recently, I’ve been working intensively with Claude (Anthropic’s AI), and something struck me: every interface Claude offers is a different kind of conversation, with different affordances and different costs.

(2) Post | LinkedIn

So I wrote a practitioner’s guide mapping Claude’s eight conversation surfaces through the lens of Gordon Pask’s Conversation Theory (1975, 1976).

The core insight: every time you switch from chat to Claude Code, or from a Project to an Artifact, you’re not just changing tools — you’re changing the structure of the conversation itself. And that structure determines what kind of knowing is possible.

The guide introduces what I call the “re-education tax” — the real cost of re-establishing shared understanding when you switch surfaces or start fresh sessions. If you’ve ever felt frustrated explaining context to an AI again after switching tools, you’ve been paying this tax without naming it.”

Differential Logic • 7

Differential Expansions of Propositions

Panoptic View • Enlargement Maps

The enlargement or shift operator exhibits a wealth of interesting and useful properties in its own right, so it pays to examine a few of the more salient features playing out on the surface of our initial example,

A suitably generic definition of the extended universe of discourse is afforded by the following set‑up.

For a proposition of the form the (first order) enlargement of

is the proposition

defined by the following equation.

The differential variables are boolean variables of the same type as the ordinary variables

Although it is conventional to distinguish the (first order) differential variables with the operational prefix

that way of notating differential variables is entirely optional. It is their existence in particular relations to the initial variables, not their names, which defines them as differential variables.

In the example of logical conjunction, the enlargement

is formulated as follows.

Given that the above expression uses nothing more than the boolean ring operations of addition and multiplication, it is permissible to “multiply things out” in the usual manner to arrive at the following result.

To understand what the enlarged or shifted proposition means in logical terms, it serves to go back and analyze the above expression for in the same way we did for

To that end, the value of

at each

may be computed in graphical fashion as shown below.

Collating the data of that analysis yields a boolean expansion or disjunctive normal form (DNF) equivalent to the enlarged proposition

Here is a summary of the result, illustrated by means of a digraph picture, where the “no change” element is drawn as a loop at the point

We may understand the enlarged proposition as telling us all the ways of reaching a model of the proposition

from the points of the universe

Resources

- Logic Syllabus

- Minimal Negation Operator

- Survey of Differential Logic

- Survey of Animated Logical Graphs

cc: Academia.edu • Cybernetics • Laws of Form • Mathstodon (1) (2)

cc: Research Gate • Structural Modeling • Systems Science • Syscoi

Jay Forrester and the Discipline That Learned to See Persistence – Damodaran (2026) (LinkedIn)

[Completing a trio of recent LinkedIn articles]

(15) Jay Forrester and the Discipline That Learned to See Persistence | LinkedIn

Sheila Damodaran

Global, National & Regional Strategy Development | Leadership Capacity, Systemic Research & Longitudinal Thinking Through The Fifth Discipline

February 1, 2026

The Great Divide: Systems Thinking and Complexity Science – Aziz (2026) (LinkedIn)

[Another one where I have great sympathy with the author and intent, but don’t agree with the piece overall – however, lots of juicy debate!]

Abdul Aziz

Strategy & Performance through Empathy, Architecture and Analytics

February 14, 2026

I recently developed a “Systems & Complexity Lifecycle” framework as a teaching device, treating systems theory, complexity science, chaos theory, and catastrophe theory as temporal stages in how entities evolve from stability through transformation.

The framework maps four stages:

Stage 1 – Systems: Stability and homeostasis (Bertalanffy’s General Systems Theory)

Stage 2 – Complexity: Emergence of higher-order properties (Holland’s Hidden Order)

Stage 3 – Chaos: Sensitivity to initial conditions (Gleick’s Chaos)

Stage 4 – Catastrophe: Discontinuous transformation (Thom’s catastrophe theory)

(4) The Great Divide: Systems Thinking and Complexity Science | LinkedIn

Peter Senge: The Fifth Discipline at Thirty-Five — Lineage, Surge, and Scale – Damodaran (2026) (LinkedIn)

Sheila Damodaran

Global, National & Regional Strategy Development | Leadership Capacity, Systemic Research & Longitudinal Thinking Through The Fifth Discipline

February 15, 2026

Peter Senge: The Fifth Discipline at Thirty-Five — Lineage, Surge, and Scale

(2) Peter Senge: The Fifth Discipline at Thirty-Five — Lineage, Surge, and Scale | LinkedIn

Sheila Damodaran

Global, National & Regional Strategy Development | Leadership Capacity, Systemic Research & Longitudinal Thinking Through The Fifth Discipline

February 15, 2026

Free 90 Minute AI Modeling Tools Workshop with Gene Bellinger – 11am EST, 19 Feb 2026

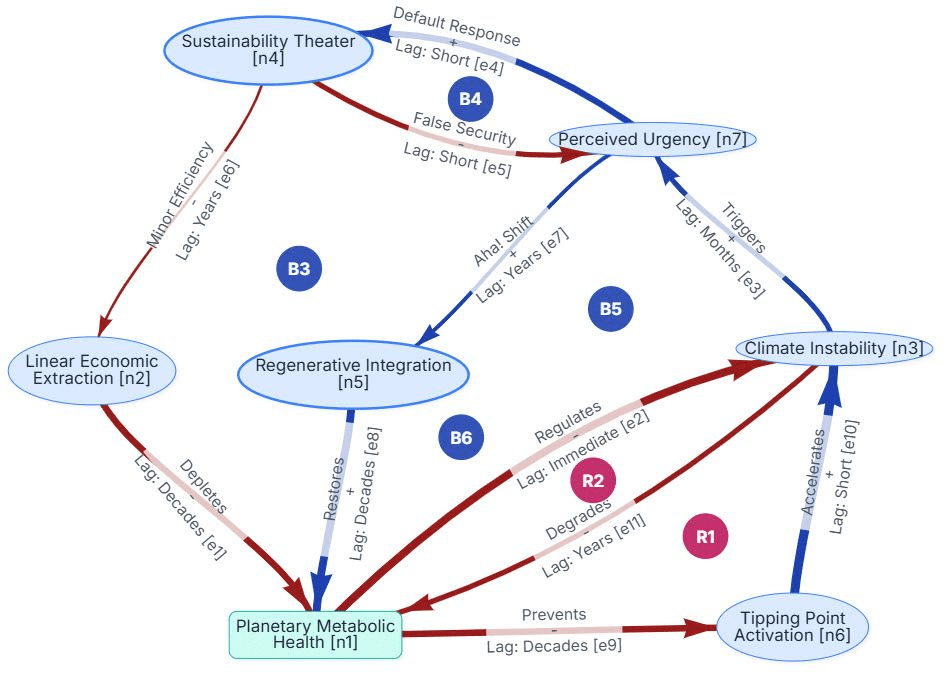

Free 90 Minute AI Modeling Tools Workshop – Create diagrams such as the one below, completely documented, along with an Aha! Paradox, and emotional story embracing the relationships, usually in 10 min or less.

Post | Feed | LinkedIn

The Workshop will be at 11 am Eastern Time (New York) on Feb 19th, and I’ll send out the Zoom link info 1 day and 1 hour before the workshop. Just reply to this post, and I’ll put you on the list.

Differential Logic • 6

Differential Expansions of Propositions

Panoptic View • Difference Maps

In the previous post we computed what is variously described as the difference map, the difference proposition, or the local proposition of the proposition

at the point

where

and

In the universe of discourse the four propositions

can be taken to indicate the so‑called “cells” or smallest distinguished regions of the universe, otherwise indicated by their coordinates as the “points”

respectively. In that regard the four propositions are called singular propositions because they serve to single out the minimal regions of the universe of discourse.

Thus we can write so long as we know the frame of reference in force.

In the example the value of the difference proposition

at each of the four points

may be computed in graphical fashion as shown below.

The easy way to visualize the values of the above graphical expressions is just to notice the following graphical equations.

Adding the arrows to the venn diagram gives us the picture of a differential vector field.

The Figure shows the points of the extended universe indicated by the difference map

namely, the following six points or singular propositions.

The information borne by should be clear enough from a survey of these six points — they tell you what you have to do from each point of

in order to change the value borne by

that is, the move you have to make in order to reach a point where the value of the proposition

is different from what it is where you started.

We have been studying the action of the difference operator on propositions of the form

as illustrated by the example

which is known in logic as the conjunction of

and

The resulting difference map

is a (first order) differential proposition, that is, a proposition of the form

The augmented venn diagram shows how the models or satisfying interpretations of distribute over the extended universe of discourse

Abstracting from that picture, the difference map

can be represented in the form of a digraph or directed graph, one whose points are labeled with the elements of

and whose arrows are labeled with the elements of

as shown in the following Figure.

Any proposition worth its salt can be analyzed from many different points of view, any one of which has the potential to reveal previously unsuspected aspects of the proposition’s meaning. We will encounter more and more such alternative readings as we go.

Resources

- Logic Syllabus

- Minimal Negation Operator

- Survey of Differential Logic

- Survey of Animated Logical Graphs

cc: Academia.edu • Cybernetics • Laws of Form • Mathstodon (1) (2)

cc: Research Gate • Structural Modeling • Systems Science • Syscoi

Differential Logic • 5

Differential Expansions of Propositions

Worm’s Eye View

Let’s run through the initial example again, keeping an eye on the meanings of the formulas which develop along the way. We begin with a proposition or a boolean function whose venn diagram and cactus graph are shown below.

A function like has an abstract type and a concrete type. The abstract type is what we invoke when we write things like

or

The concrete type takes into account the qualitative dimensions or “units” of the case, which can be explained as follows.

Let be the set of values

Let be the set of values

Then interpret the usual propositions about as functions of the concrete type

We are going to consider various operators on these functions. An operator is a function which takes one function

into another function

The first couple of operators we need are logical analogues of two which play a founding role in the classical finite difference calculus, namely, the following.

The difference operator written here as

The enlargement operator, written here as

These days, is more often called the shift operator.

In order to describe the universe in which these operators operate, it is necessary to enlarge the original universe of discourse. Starting from the initial space its (first order) differential extension

is constructed according to the following specifications.

where:

The interpretations of these new symbols can be diverse, but the easiest option for now is just to say means “change

” and

means “change

”.

Drawing a venn diagram for the differential extension requires four logical dimensions,

but it is possible to project a suggestion of what the differential features

and

are about on the 2‑dimensional base space

by drawing arrows crossing the boundaries of the basic circles in the venn diagram for

reading an arrow as

if it crosses the boundary between

and

in either direction and reading an arrow as

if it crosses the boundary between

and

in either direction, as indicated in the following figure.

Propositions are formed on differential variables, or any combination of ordinary logical variables and differential logical variables, in the same ways propositions are formed on ordinary logical variables alone. For example, the proposition says the same thing as

in other words, there is no change in

without a change in

Given the proposition over the space

the (first order) enlargement of

is the proposition

over the differential extension

defined by the following formula.

In the example the enlargement

is computed as follows.

Given the proposition over

the (first order) difference of

is the proposition

over

defined by the formula

or, written out in full:

In the example the difference

is computed as follows.

This brings us by the road meticulous to the point we reached at the end of the previous post. There we evaluated the above proposition, the first order difference of conjunction at a single location in the universe of discourse, namely, at the point picked out by the singular proposition

in terms of coordinates, at the place where

and

That evaluation is written in the form

or

and we arrived at the locally applicable law which may be stated and illustrated as follows.

The venn diagram shows the analysis of the inclusive disjunction into the following exclusive disjunction.

The differential proposition may be read as saying “change

or change

or both”. And this can be recognized as just what you need to do if you happen to find yourself in the center cell and require a complete and detailed description of ways to escape it.

Resources

- Logic Syllabus

- Minimal Negation Operator

- Survey of Differential Logic

- Survey of Animated Logical Graphs

cc: Academia.edu • Cybernetics • Laws of Form • Mathstodon (1) (2)

cc: Research Gate • Structural Modeling • Systems Science • Syscoi

Request for votes for interactive skills training workshops at Systems Thinking Systems Practice conference, 24-26 March 2026, University of Hull

At Systems Thinking Systems Practice, 24-26 March 2026, University of Hull, we will again run Skills Training Workshops.

These workshops were a huge success at SysPrac25, with many of them oversubscribed.

They will take the form of interactive workshops, which will further develop your skills or introduce you to new approaches you may not have encountered before.

To vote visit https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSfsLoKstfeA5BwI8pK5kAb25abdUAhLeKe2s51Xp4Gmxw_FAg/viewform before 20 February 2026!

The conference: https://stream.syscoi.com/2026/01/25/2026-conference-systems-thinking-and-systems-practice-hosted-by-the-university-of-hull-centre-for-systems-studies-css-systems-and-complexity-in-organisation-scio-and-the-or-society-24-26-march/

Complex Systems Frameworks Collection

Complex Systems Frameworks Collection

Frameworks A-Z – Complex Systems Frameworks Collection

The Game

THE GAME

The Game – Birmingham Food Council

Storytelling for Systems Change

New website

Storytelling for Systems Change

Storytelling for Systems Change – Dusseldorp Forum

A story-kit for changemakers

You must be logged in to post a comment.