Am asking for a friend.

Monthly Archives: March 2019

How to Make Swarms Open-Ended? Evolving Collective Intelligence Through a Constricted Exploration of Adjacent Possibles

We propose an approach of open-ended evolution via the simulation of swarm dynamics. In nature, swarms possess remarkable properties, which allow many organisms, from swarming bacteria to ants and flocking birds, to form higher-order structures that enhance their behavior as a group. Swarm simulations highlight three important factors to create novelty and diversity: (a) communication generates combinatorial cooperative dynamics, (b) concurrency allows for separation of timescales, and (c) complexity and size increases push the system towards transitions in innovation. We illustrate these three components in a model computing the continuous evolution of a swarm of agents. The results, divided in three distinct applications, show how emergent structures are capable of filtering information through the bottleneck of their memory, to produce meaningful novelty and diversity within their simulated environment.

How to Make Swarms Open-Ended? Evolving Collective Intelligence Through a Constricted Exploration of Adjacent Possibles

Olaf Witkowski, Takashi Ikegami

Source: arxiv.org

Exploitation and Exploration | strategic structures

Source: Exploitation and Exploration | strategic structures

Exploitation and Exploration

![]()

I love going to jazz festivals. Listening to good jazz at home is enjoyable, but there is something special about the electricity that sparks during a live performance. And it’s not the same when you listen to a recording of a concert. It is completely different when you are actually there, immersed, experiencing directly with all your senses. I guess it’s similar with other types of music. But what makes the difference between listening to a recording and being at concert even bigger for jazz, is that it is all about improvisation. And then the experience with single concerts and festivals is also different. With concerts, you immerse yourself for a couple of hours into that magic and then go back to the normal world. But with jazz festivals, you relocate to live in a music village for a couple of days. This doesn’t only make it a different experience, but also calls for a different kind of decision.

Previously, when I learned of a new jazz festival or read the line-up of a familiar one, the way I decided whether to go was simple. I just checked who would be performing. If there were musicians that I liked, but hadn’t watched live, or some that I had but wanted to see again, then I went. If not, I usually wouldn’t risk it.

Once I chose to go, this brought another set of decisions. Jazz festivals usually have many stages with concerts going in parallel during the day and into the night. Last time I went to the North Sea Jazz Festival there were over eighty performances in only a few days. So there is a good chance that some of those you want to watch will clash, and you are forced to choose. And I kept applying the same low-risk strategy for choosing what to watch as I did for deciding if I should go at all.

Then one day, I arrived late to a festival just before two clashing sets were about to begin. I dashed into the closest hall with no clue what I would find. And there I experienced what turned out to be the best concert of the whole festival. I hadn’t heard of the group and if I had read the description beforehand I would have avoided their performance.

I realised then, by only choosing concerts with familiar musicians, I was over-exploiting and under-exploring. My strategy was depriving me of learning opportunities and overall reduced the value I got from the festivals.

Continues in source: Exploitation and Exploration | strategic structures

Henri Bortoft’s 2010 Schumacher College lectures

“Taking Appearance Seriously is a rare philosophical work of both outstanding quality and immense practicality, written to guide the reader into really experiencing what Henri Bortoft calls the dynamic way of seeing: a radically aware way of thinking and comprehending our complex world which is as applicable in the creative arts and business world as it is in science.”

“Taking Appearance Seriously is a rare philosophical work of both outstanding quality and immense practicality, written to guide the reader into really experiencing what Henri Bortoft calls the dynamic way of seeing: a radically aware way of thinking and comprehending our complex world which is as applicable in the creative arts and business world as it is in science.”

Simon Robinson

Many of you will have seen that last year I published the complete set of Henri Bortoft’s 2009 lectures from Schumacher College. In order not to repeat myself too much, you may wish to read my introduction to this series. I also published a final article which explored how Maria and I are putting Henri’s philosophy and teachings into practice, in various organisational contexts such as cultural transformation, innovation, change management and customer experience design.

I am therefore extremely happy to be able to announce the publication…

View original post 211 more words

Systemic evaluation design

Currently Bob Williams is preparing the second edition of his workbook on ‘Using systems concepts in evaluation design’ (available as a pdf for only 5$ from https://gumroad.com/l/evaldesign). It describes a practical systems approach to evaluation design. As Churchman explains in chapter 1 of “The systems approach” (available here), his dialectical systems approach was designed to first of all think about the function of systems, human systems such as organizations, policies and projects in particular, to reflect on their “overall objective and then to begin to describe the system in terms of this overall objective.” You may not be aware of it, but this is as revolutionary an idea today as it was more than half a century ago. It applies as much to systemic design as to systemic evaluation. The main take-away is that one cannot decide on an evaluation method without first looking into half a dozen…

View original post 1,249 more words

SCiO Open Meeting – Spring 2019, Manchester, Mon 8 Apr 2019 at 09:30

APR 08

SCiO Open Meeting – Spring 2019, Manchester (All Welcome)

by SCiO – Systems and Complexity in Organisation

£20

An open meeting where a series of presentations of general interest regarding systems practice will be given – this will include ‘craft’ and active sessions, as well as introductions to theory. Please note that the meeting has moved ‘back’ into the new main MBS building.

Session: Keekok Lee; Why 21st century is the century of Systems Thinking

This talk examines System Thinking by exploring the following themes:

- System Thinking is embedded within a philosophical framework which is totally different from that of so-called “standard thinking” found in what may be called the Newtonian sciences, such as classical physics, DNA/ molecular biology, the monogenic conception of disease in Biomedicine, and so on.

2. Modern science beginning in the 17th century in Western Europe (which was/is Newtonian) suffered a rupture in its philosophical orientation at least thrice in the 20th century: quantum physics from the 1920s onwards, the establishment of ecology as well as the emergence of Epidemiology as proper scientific disciplines in the last century, the former at the end of WWII and the latter in the last quarter of the 20th century. The 21st century may well turn out to be the century of Systems Thinking, of the triumph of non-/not-Newtonian sciences.

3. The oldest form of Systems Thinking in world history may be found inThe Yijing/I Chingas well as in Classical Chinese Medicine whose foundation rests on the insights of The Yijing/I Ching, the most well-known is the iconic Yinyang symbol. These basic insights include: Process-ontology, Wholism, non-linear/multi-factorial causality.

4. In my opinion, Systems Thinking could more tellingly be re-labelled “Ecosystem Thinking” as any phenomenon under study could best be portrayed as a nesting of ecosystems, the smaller within a larger. The benefit of this new presentation of data will be illustrated by one particular example from Classical Chinese Medicine.

Session: Ray Ison; How is Systemic Change different?

Claims are frequently made about changing THE system. Many talk about Whole System change. Then there is systematic change as well as systemic change. What do practitioners do when they engage, or claim that they engage, with these types of change? What are the elements of systemic praxis (theory informed practical action)? What are the implications for the use of methods and methodologies? And for situational change which constitutes an improvement? Ray will draw on his experiences of designing successful modules within the STiP (systems thinking in practice) program at the Open University as well as his own research/consultancy praxis to explore what it means to become a reflexive practitioner of systemic change.

Session: Robin Stowell; From Perilous Ignorance to Autonomous Safety

If your occupational health and safety policy states a commitment to providing a safe workplace, reporting accidents, continual improvement etc. have you considered this from a cybernetic viewpoint?

Most organisations govern their safety management by trying to achieve Zero Harm through implementing corporate risk assessments, but accidents still happen, and management hunts down someone to blame for poor safety statistics on the management review dashboard. The system hasn’t failed, it is doing what it has been designed (and allowed) to do. How do the requirements of safety management system standards integrate into the Viable System Model?

Variety, and in particular the requisite variety needed in operations to counter unwanted states in the local environment (accidents), has never been considered before from a safety perspective. This presentation will propose that requisite variety of an individual worker can be directly equated to competence, and furthermore through assessment of the person-task it provides the basis for a real-time safety performance monitoring and control mechanism

Session: Ian Kendrick: Three Horizons – Concept & Practice

details to be provided.

Mon, 8 April 2019 09:30 – 17:00 BST

Location

Rm 3.008, Alliance Manchester Business School, Booth Street West, Manchester M15 6PB

OrganiserSCiO – Systems And Complexity In Organisation

Organiser of SCiO Open Meeting – Spring 2019, Manchester (All Welcome)

SCiO is a group for systems practitioners and is based in the UK, but has members internationally.

Two of the features that distinguish SCiO from other systems groups are that it is focused primarily on systems practice and practitioners rather than on pure theory and that it is focused on systems practice applied to issues of organisation.

It has three main objectives:

Developing practice in applying systems ideas to a range of organisational issues.

Disseminating the use of systems approaches in dealing with organisational issues.

Supporting practitioners in their professional practice.

SCiO is a social enterprise and a not for profit organisation which is owned by its members.

Provenance and Purpose.

Created initally by a network of practitioners in the North of England, SCiO acts as an extra channel for disseminating to others their experience of practical applications, education and research in complex problem solving. The name stands for ‘Systems and Complexity in Organisation’ but can also be thought of as short for the ‘Science of Organisation’.

Over the last sixty years the new disciplines of ‘Systems Thinking’ and ‘Managerial Cybernetics’ have emerged. The new thinking started from the consideration of complex problems faced during the Second World War; then later in the 1970’s the same patterns of thinking emerged with the new awareness of the complexity of ecological problems. The ideas developed and spread into other areas of science and in particular into management. In the last thirty years new insights and understanding have developed in the way to approach apparently intractable problems in many areas.

At this time the terms ‘whole systems approach’ and ‘systems thinking’ seem to be appearing more frequently in published policy documents and guidance on best practice in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, such as in the UK National Health Service; in documents on public health, sustainable communities, in education, in considerations of the environment, and in corporate governance.

The members of SCiO believe that the use of systems thinking and managerial cybernetics can have major impacts on the well-being of our communities, and our business and social organisations.

A manifesto of interdisciplinarity

Integration and Implementation Insights

Community member post by Rick Szostak

Rick Szostak (biography)

Rick Szostak (biography)

Is there a shared understanding of what interdisciplinarity is and how (and why) it is best pursued that can be used by the international community of scholars of interdisciplinarity, to both advocate for and encourage interdisciplinary scholarship? Is there consensus on what we are trying to achieve and how this is best done that can form the basis of cogent advice to interdisciplinary teachers and researchers regarding strategies that have proven successful in the past?

I propose a ‘Manifesto of Interdisciplinarity’ with nine brief points, as listed below. These are drawn from the original version at: https://sites.google.com/a/ualberta.ca/manifesto-of-interdisciplinarity/manifesto-of-interdisciplinarity, where key points are linked to more extended conversations, which in turn are linked to the wider literature. The nine points address what interdisciplinarity is, why it is important, and how it is best pursued.

The Manifesto

- The essential feature of…

View original post 787 more words

Full Stack Systems Thinking

I’ve figured out a name for what I do. It’s Full Stack Systems. It’s important to have a name for things, so we can notice them, and can choose to notice them. I’ve borrowed Full Stack from the IT term Full Stack Developer, meaning someone with the skills to program back end and front end systems, and who understands the full delivery model of their work.

Full Stack Systems Thinking looks at the connections between things as much as the things themselves. It looks at patterns, emergence, interconnectedness and other systemic stuff.

Going up the stack

- Knowing Myself, knowing the patterns I use, the internal dramas I have

- Understanding the way groups interact at their best and worst, and how they can work in curiosity or contempt

- Challenging my own and others Theories in Use and Theories in Practice

- Seeing how groups interact, and the patterns and drama…

View original post 158 more words

Jeff at Kumu has a newsletter – and a podcast! This Month at Kumu: In Too Deep Podcast | Quick Tips | System Mapping Webinar

https://kumu.io/ – systems mapping

blog https://blog.kumu.io/ (via Medium)

community https://kumu.io/community

slack http://chat.kumu.io/

sign up for the newsletter – like below – https://confirmsubscription.com/h/t/6B8ACB72A9EECA3F

In Too Deep Podcast: New Episodes

This month we have two new interviews on the In Too Deep podcast with Sam Rye and Luke Craven that you won’t want to miss.

In our conversation with Sam Rye we touch on a variety of topics – from the role of nature in encouraging greater presence, the importance of an experimental focus, how to combine systems analysis, strategy and prototyping, and why we need to focus far more on relationships.

Luke Craven shares his systems effects methodology, some of the challenges in traditional systems mapping, and secrets for how to bring more of a user understanding of complex systems into social science and policy making practice.

And if you missed our first four episodes, you can listen to them here or search for “In Too Deep” wherever you get your podcasts.

Quick Tips

If you’ve browsed the Kumu docs, you might have stumbled across our Quick Tips, a playlist of 2-5 minute video tutorials on different Kumu concepts and skills. We recently started recording more quick tips; here are some of the latest entries:

Webinar: Mapping the News

Ever read a complex news article and felt like you didn’t quite grasp all the details? Alex (head of customer support at Kumu) has, and he’s come up with a solution: turn the article into a system map!

In a webinar on Tuesday, April 23 at 10am PDT, Alex will demo his approach to mapping articles and talk through some of our thoughts on how to make system maps more readable and approachable. Here are a few resources if you want to dive in ahead of time:

Embodied Dyadic Interaction Increases Complexity of Neural Dynamics: A Minimal Agent-Based Simulation Model

The concept of social interaction is at the core of embodied and enactive approaches to social cognitive processes, yet scientifically it remains poorly understood. Traditionally, cognitive science had relegated all behavior to being the end result of internal neural activity. However, the role of feedback from the interactions between agent and their environment has become increasingly important to understanding behavior. We focus on the role that social interaction plays in the behavioral and neural activity of the individuals taking part in it. Is social interaction merely a source of complex inputs to the individual, or can social interaction increase the individuals’ own complexity? Here we provide a proof of concept of the latter possibility by artificially evolving pairs of simulated mobile robots to increase their neural complexity, which consistently gave rise to strategies that take advantage of their capacity for interaction. We found that during social interaction, the neural controllers…

View original post 127 more words

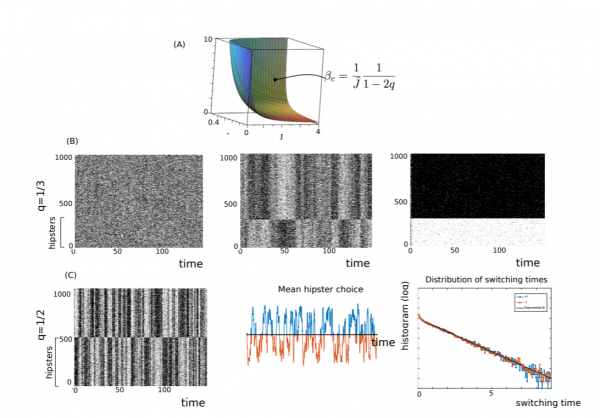

The hipster effect: Why anti-conformists always end up looking the same – MIT Technology Review

via Complexity Digest

Source: The hipster effect: Why anti-conformists always end up looking the same – MIT Technology Review

The hipster effect: Why anti-conformists always end up looking the same

Complexity science explains why efforts to reject the mainstream merely result in a new conformity.

And yet when you finally reveal your new look to the world, it turns out you are not alone—millions of others have made exactly the same choices. Indeed, you all look more or less identical, the exact opposite of the countercultural statement you wanted to achieve.

This is the hipster effect—the counterintuitive phenomenon in which people who oppose mainstream culture all end up looking the same. Similar effects occur among investors and in other areas of the social sciences.

How does this kind of synchronization occur? Is it inevitable in modern society, and are there ways for people to be genuinely different from the masses?

Today we get some answers thanks to the work of Jonathan Touboul at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. Touboul is a mathematician who studies the way the transmission of information through society influences the behavior of people within it. He focuses in particular on a society composed of conformists who copy the majority and anticonformists, or hipsters, who do the opposite.

And his conclusion is that in a vast range of scenarios, the hipster population always undergoes a kind of phase transition in which members become synchronized with each other in opposing the mainstream. In other words, the hipster effect is the inevitable outcome of the behavior of large numbers of people.

Crucially, Toubol’s model takes into account the time needed for each individual to detect changes in society and to react accordingly. This delay is important. People do not react instantly when a new, highly fashionable pair of shoes becomes available. Instead, the information spreads slowly via fashion websites, word of mouth, and so on. This propagation delay is different for individuals, some of whom may follow fashion blogs religiously while others have no access to them and have to rely on word of mouth.

The question that Touboul investigates is under what circumstances hipsters become synchronized and how this varies as the propagation delay and the proportion of hipsters both change. He does this by creating a computer model that simulates how agents interact when some follow the majority and the rest oppose it.

This simple model generates some fantastically complex behaviors. In general, Touboul says, the population of hipsters initially act randomly but then undergo a phase transition into a synchronized state. He finds that this happens for a wide range of parameters but that the behavior can become extremely complex, depending on the way hipsters interact with conformists.

There are some surprising outcomes, too. When there are equal proportions of hipsters and conformists, the entire population tends to switch randomly between different trends. Why isn’t clear, and Touboul wants to study this in more detail.

It can be objected that the synchronization stems from the simplicity of scenarios offering a binary choice. “For example, if a majority of individuals shave their beard, then most hipsters will want to grow a beard, and if this trend propagates to a majority of the population, it will lead to new, synchronized, switch to shaving,” says Touboul.

It’s easy to imagine a different outcome if there are more choices. If hipsters could grow a mustache, a square beard, or a goatee, for example, then perhaps this diversity of choice would prevent synchronization. But Touboul has found that when his model offers more than two choices, it still produces the synchronization effect.

Nevertheless, he wants to study this further. “We will study in depth this question in a forthcoming paper,” he says.

Hipsters are an easy target for a bit of fun, but the results have much wider applicability. For example, they could be useful for understanding financial systems in which speculators attempt to make money by taking decisions that oppose the majority in a stock exchange.

Indeed, there are many areas in which delays in the propagation of information play an important role: As Touboul puts it: “Beyond the choice of the best suit to wear this winter, this study may have important implications in understanding synchronization of nerve cells, investment strategies in finance, or emergent dynamics in social science.”

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1410.8001 : The Hipster Effect: When Anti-Conformists All Look the Same

ISSS conference2019, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA 28 JUNE – 2 JULY 2019| International Society for the Systems Sciences

Source: ISSS2019, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. | International Society for the Systems Sciences=

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

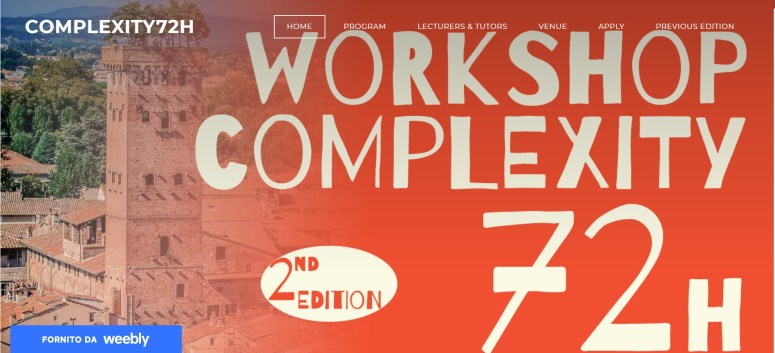

2nd Workshop Complexity72H! 17-21 June 2019 at IMT Lucca, Italy.

The workshop Complexity72h is an interdisciplinary event whose aim is to bring together young researchers from different fields of complex systems.

Inspired by the 72h Hours of Science, participants will form working groups aimed at carrying out a project in a three-day time, i.e. 72 hours. Each group’s goal is to upload on the arXiv a report of their work by the end of the event. A team of tutors will propose the projects, and assist and guide each group in developing their project.

Alongside teamwork, participants will attend lectures from scientists coming from different fields of complex systems, and applied workshops.

The workshop is organized and will be hosted by the IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca.

Wanna know more? Send us an email at complexity72h [at] gmail [dot] com

Source: complexity72h.weebly.com

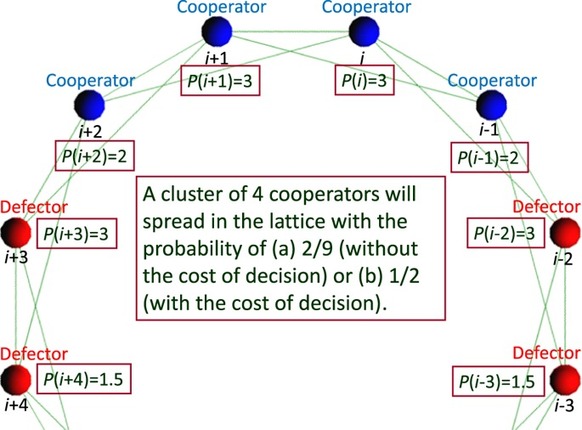

Coevolution between the cost of decision and the strategy contributes to the evolution of cooperation

Cooperation is still an important issue for both evolutionary and social scientists. There are some remarkable methods for sustaining cooperation. On the other hand, various studies discuss whether human deliberative behaviour promotes or inhibits cooperation. As those studies of human behaviour develop, in the study of evolutionary game theory, models considering deliberative behaviour of game players are increasing. Based on that trend, the author considers that decision of a person requires certain time and imposes a psychological burden on him/her and defines such burden as the cost of decision. This study utilizes the model of evolutionary game theory that each player plays the spatial prisoner’s dilemma game with opponent players connected to him/her and introduces the cost of decision. The main result of this study is that the introduction of the cost of decision contributes to the evolution of cooperation, although there are some differences in the extent of its…

View original post 74 more words

Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity | Management Science / Operations Research | Management | Business & Management | Subjects | Wiley

This is a biggie, in at least two senses! Mike Jackson says this is twice the size and completely reworked, though following the same schema as the original edition (actually – different title – systems thinking: creative holism for managers)

Availability/launch date in the UK 22 March.

Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity

ISBN: 978-1-119-11837-4 March 2019 728 Pages

DESCRIPTION

The world has become increasingly networked and unpredictable. Decision makers at all levels are required to manage the consequences of complexity every day. They must deal with problems that arise unexpectedly, generate uncertainty, are characterised by interconnectivity, and spread across traditional boundaries. Simple solutions to complex problems are usually inadequate and risk exacerbating the original issues.

Leaders of international bodies such as the UN, OECD, UNESCO and WHO — and of major business, public sector, charitable, and professional organizations — have all declared that systems thinking is an essential leadership skill for managing the complexity of the economic, social and environmental issues that confront decision makers. Systems thinking must be implemented more generally, and on a wider scale, to address these issues.

An evaluation of different systems methodologies suggests that they concentrate on different aspects of

complexity. To be in the best position to deal with complexity, decision makers must understand the strengths and weaknesses of the various approaches and learn how to employ them in combination. This is called critical systems thinking. Making use of over 25 case studies, the book offers an account of the development of systems thinking and of major efforts to apply the approach in real-world interventions. Further, it encourages the widespread use of critical systems practice as a means of ensuring responsible leadership in a complex world.

Comments on a previous version of the book:

Russ Ackoff: ‘the book is the best overview of the field I have seen’

JP van Gigch: ‘Jackson does a masterful job. The book is lucid …well written and eminently readable’

Professional Manager (Journal of the Chartered Management Institute): ‘Provides an excellent guide and introduction to systems thinking for students of management’

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface xvii

Introduction xxv

Part I Systems Thinking in the Disciplines 1

1 Philosophy 3

1.1 Introduction 3

1.2 Kant 4

1.3 Hegel 8

1.4 Pragmatism 9

1.5 Husserl and Phenomenology 10

1.6 Radical Constructivism 11

1.7 Conclusion 12

2 The Physical Sciences and the Scientific Method 15

2.1 Introduction 15

2.2 The Scientific Method and the Scientific Revolution 16

2.3 The Physical Sciences in the Modern Era 19

2.4 The Scientific Method in the Modern Era 21

2.5 Extending the Scientific Method to Other Disciplines 24

2.6 Conclusion 25

3 The Life Sciences 27

3.1 Introduction 27

3.2 Biology 27

3.3 Ecology 35

3.4 Conclusion 40

4 The Social Sciences 43

4.1 Introduction 43

4.2 Functionalism 44

4.3 Interpretive Social Theory 49

4.4 The Sociology of Radical Change 52

4.5 Postmodernism and Poststructuralism 56

4.6 Integrationist Social Theory 59

4.7 Luhmann’s Social Systems Theory 62

4.8 Action Research 67

4.9 Conclusion 68

Part II The Systems Sciences 71

5 General Systems Theory 75

5.1 Introduction 75

5.2 von Bertalanffy and General System Theory 75

5.3 von Bertalanffy’s Collaborators and the Society for General Systems Research 79

5.4 Miller and the Search for Isomorphisms at Different System Levels 80

5.5 Boulding, Emergence and the Centrality of “The Image” 82

5.6 The Influence of General Systems Theory 85

5.7 Conclusion 86

6 Cybernetics 89

6.1 Introduction 89

6.2 First‐Order Cybernetics 91

6.3 British Cybernetics 95

6.4 Second‐Order Cybernetics 102

6.5 Conclusion 108

7 Complexity Theory 111

7.1 Introduction 111

7.2 Chaos Theory 112

7.3 Dissipative Structures 117

7.4 Complex Adaptive Systems 119

7.5 Complexity Theory and Management 125

7.6 Complexity Theory and Systems Thinking 136

7.7 Conclusion 144

Part III Systems Practice 147

8 A System of Systems Methodologies 151

8.1 Introduction 151

8.2 Critical or “Second‐Order” Systems Thinking 152

8.3 Toward a System of Systems Methodologies 155

8.3.1 Preliminary Considerations 155

8.3.2 Beer’s Classification of Systems 155

8.3.3 The Original “System of Systems Methodologies” 157

8.3.4 Snowden’s Cynefin Framework 160

8.3.5 A Revised “System of Systems Methodologies” 162

8.4 The Development of Applied Systems Thinking 166

8.5 Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity 169

8.6 Conclusion 169

Type A Systems Approaches for Technical Complexity 171

9 Operational Research, Systems Analysis, Systems Engineering (Hard Systems Thinking) 173

9.1 Prologue 173

9.2 Description of Hard Systems Thinking 175

9.2.1 Historical Development 175

9.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 177

9.2.3 Methodology 179

9.2.4 Methods 182

9.2.5 Developments in Hard Systems Thinking 184

9.3 Hard Systems Thinking in Action 188

9.4 Critique of Hard Systems Thinking 191

9.5 Comments 196

9.6 The Value of Hard Systems Thinking to Managers 197

9.7 Conclusion 197

Type B Systems Approaches for Process Complexity 199

10 The Vanguard Method 201

10.1 Prologue 201

10.2 Description of the Vanguard Method 203

10.2.1 Historical Development 203

10.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 206

10.2.3 Methodology 209

10.2.4 Methods 211

10.3 The Vanguard Method in Action 212

10.3.1 Check 213

10.3.2 Plan 215

10.3.3 Do 216

10.4 Critique of the Vanguard Method 220

10.5 Comments 224

10.6 The Value of the Vanguard Method to Managers 225

10.7 Conclusion 226

Type C Systems Approaches for Structural Complexity 227

11 System Dynamics 229

11.1 Prologue 229

11.2 Description of System Dynamics 231

11.2.1 Historical Development 231

11.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 233

11.2.3 Methodology 241

11.2.4 Methods 244

11.3 System Dynamics in Action 247

11.4 Critique of System Dynamics 249

11.5 Comments 258

11.6 The Value of System Dynamics to Managers 258

11.7 Conclusion 259

Type D Systems Approaches for Organizational Complexity 261

12 Socio‐Technical Systems Thinking 263

12.1 Prologue 263

12.2 Description of Socio‐Technical Systems Thinking 264

12.2.1 Historical Development 264

12.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 268

12.2.3 Methodology 276

12.2.4 Methods 279

12.3 Socio‐Technical Systems Thinking in Action 280

12.4 Critique of Socio‐Technical Systems Thinking 281

12.5 Comments 288

12.6 The Value of Socio‐Technical Systems Thinking to Managers 289

12.7 Conclusion 289

13 Organizational Cybernetics and the Viable System Model 291

13.1 Prologue 291

13.2 Description of Organizational Cybernetics 296

13.2.1 Historical Development 296

13.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 299

13.2.3 Methodology 311

13.2.4 Methods 317

13.3 Organizational Cybernetics in Action 320

13.4 Critique of Organizational Cybernetics and the Viable System Model 325

13.5 Comments 337

13.6 The Value of Organizational Cybernetics to Managers 339

13.7 Conclusion 340

Type E Systems Approaches for People Complexity 341

14 Strategic Assumption Surfacing and Testing 343

14.1 Prologue 343

14.2 Description of Strategic Assumption Surfacing and Testing 346

14.2.1 Historical Development 346

14.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 348

14.2.3 Methodology 353

14.2.4 Methods 355

14.3 Strategic Assumption Surfacing and Testing in Action 357

14.4 Critique of Strategic Assumption Surfacing and Testing 360

14.5 Comments 365

14.6 The Value of Strategic Assumption Surfacing and Testing to Managers 366

14.7 Conclusion 367

15 Interactive Planning 369

15.1 Prologue 369

15.2 Description of Interactive Planning 371

15.2.1 Historical Development 371

15.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 375

15.2.3 Methodology 379

15.2.4 Methods 382

15.3 Interactive Planning in Action 384

15.4 Critique of Interactive Planning 388

15.5 Comments 394

15.6 The Value of Interactive Planning to Managers 395

15.7 Conclusion 395

16 Soft Systems Methodology 397

16.1 Prologue 397

16.2 Description of Soft Systems Methodology 401

16.2.1 Historical Development 401

16.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 404

16.2.3 Methodology 411

16.2.4 Methods 420

16.3 Soft Systems Methodology in Action 427

16.4 Critique of Soft Systems Methodology 431

16.5 Comments 441

16.6 The Value of Soft Systems Methodology to Managers 442

16.7 Conclusion 443

Type F Systems Approaches for Coercive Complexity 445

17 Team Syntegrity 447

17.1 Prologue 447

17.2 Description of Team Syntegrity 449

17.2.1 Historical Development 449

17.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 450

17.2.3 Methodology 455

17.2.4 Methods 458

17.3 Team Syntegrity in Action 459

17.4 Critique of Team Syntegrity 462

17.5 Comments 468

17.6 The Value of Team Syntegrity to Managers 470

17.7 Conclusion 470

18 Critical Systems Heuristics 471

18.1 Prologue 471

18.2 Description of Critical Systems Heuristics 473

18.2.1 Historical Development 473

18.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 476

18.2.3 Methodology 479

18.2.4 Methods 484

18.3 Critical Systems Heuristics in Action 485

18.4 Critique of Critical Systems Heuristics 490

18.5 Comments 502

18.6 The Value of Critical Systems Heuristics to Managers 508

18.7 Conclusion 509

Part IV Critical Systems Thinking 511

19 Critical Systems Theory 515

19.1 Introduction 515

19.2 The Origins of Critical Systems Theory 516

19.2.1 Critical Awareness 517

19.2.2 Pluralism 519

19.2.3 Emancipation or Improvement 522

19.3 Critical Systems Theory and the Management Sciences 524

19.4 Conclusion 528

20 Critical Systems Thinking and Multimethodology 531

20.1 Introduction 531

20.2 Total Systems Intervention 540

20.2.1 Background 540

20.2.2 Multimethodology 541

20.2.3 Case Study 545

20.2.4 Critique 553

20.3 Systemic Intervention 558

20.3.1 Background 558

20.3.2 Multimethodology 559

20.3.3 Case Study 562

20.3.4 Critique 565

20.4 Critical Realism and Multimethodology 568

20.4.1 Background 568

20.4.2 Multimethodology 570

20.4.3 Case Study 572

20.4.4 Critique 572

20.5 Conclusion 576

21 Critical Systems Practice 577

21.1 Prologue 577

21.2 Description of Critical Systems Practice 579

21.2.1 Historical Development 579

21.2.2 Philosophy and Theory 581

21.2.3 Multimethodology 593

21.2.4 Methodologies 601

21.2.5 Methods 604

21.3 Critical Systems Practice in Action 607

21.3.1 North Yorkshire Police 607

21.3.2 Kingston Gas Turbines 617

21.3.3 Hull University Business School 621

21.4 Critique of Critical Systems Practice 632

21.5 Comments 637

21.6 The Value of Critical Systems Practice to Managers 638

21.7 Conclusion 638

Conclusion 641

References 645

Index 679

You must be logged in to post a comment.